|

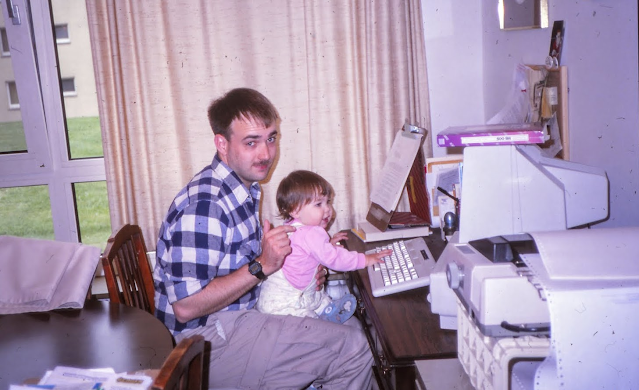

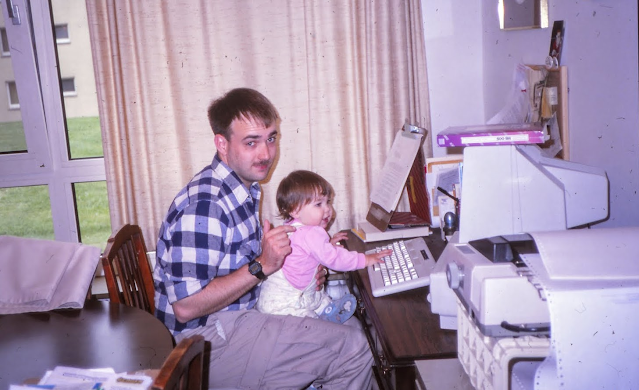

| My daughter and I playing on my Tandy 1000, around 1986 |

I grew to adulthood with computers. Born a year before Sputnik, I grew up in an era where American technical prowess was unmatched, and computers were at the center of everything. My friends and I were fascinated by science and engineering. In our world guys with slide rules weren't geeks, they were cool. Computers filled rooms (really, they did) and dispensed digital wisdom codified in stacks of fanfold paper and blinking lights. To be allowed to just approach a computer terminal was the equivalent of approaching the high altar in a cathedral. "Come forward my son, but only with fear and awe in your heart."

I didn't get access to a computer for serious work until my sophomore year in college, spending hours on the university's time share system running epidemiological 'what-if' analysis of some unknown mosquito-borne disease. The goal was to kill off the vectors before the vectors killed off the hosts, and it was a surprisingly grim simulation of how fast mosquitoes can spread disease. Suffice to say, the poor residents of the mythical town in South America didn't fare too well when I was at the keyboard.

I graduated in 1979 and was soon in the Army and training to be an Engineer officer. At Fort Belvoir we were introduced to the Engineer School's IBM time-share system, learning to run some rudimentary engineering analysis and project scheduling software, and also dabbling in a bit of Basic programming. This was at the dawn of the PC era; Apple had released the Apple II just two years before, and the first IBM PC would hit the market in 1981. Of course both machines were way beyond the means of any newly minted second lieutenant. An Apple II sold in 1977 for the equivalent of over $6,300 in today's dollars. Most of us made do with lesser forms of computing - the Timex/Sinclair 1000, various Atari, Commodore and Radio Shack models, etc. These were all technically computers, but in reality were little more than souped-up game machines pointed at the home market.

When the first IBM PC hit the market, it hit with a bang. Here was IBM 'big iron' in tabletop format. Ignore the fact that the CPU was a wheezy Intel 8088, the graphics were a joke, many home game consoles came with more RAM, and the operating system, PC-DOS, had been hastily cobbled together by a couple of kids working out of a Seattle area office. None of that really mattered. What led to the PC's market dominance was its open system architecture. Anyone could develop add-on hardware and write software to expand and improve the PC's performance. The only thing IBM kept proprietary was the system BIOS. The PC add-on market took off like a rocket. Plus, although PCs were expensive, they were seen as a safe bet in the corporate world. After all, they were IBMs, and

nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.

|

Today the IBM-PC layout looks ho-hum, but in the early 1980s it was groundbreaking

and set the standard for most personal computers that followed |

The IBM-PC was such a hit that the inevitable quickly followed. Competing manufacturers figured out how to reverse engineer the BIOS - reproducing instruction sets that did the same thing the IBM BIOS did, but doing it differently to avoid IBM's patents. Compaq was the first competitor to get this figured out. Less than a year after the PC appeared you could buy PC clones that ran non-IBM versions of PC-DOS, something called MS-DOS, developed and sold by the same kids in Seattle who had renamed their company to Microsoft.

By 1985 I was using IBM-PCs in my work, and I badly wanted my own PC to use at home. But even the clones were pricey. While there may not have been honor among hardware and software pirates, everyone understood the market value of what they were making (or stealing). Even the early clones like the Compaq PCs were beyond my reach. Then, in early 1984, I picked up a computer magazine and spotted something interesting - Tandy (the company that owned Radio Shack) had announced a low cost PC clone called the Tandy 1000. Over the course of the next few months I eagerly followed its progress, reading the reviews, catching the articles in all the magazines. The Tandy 1000 was considered a home computer, but it was a true IBM-PC clone that ran MS-DOS. With few exceptions it could run almost every software application written for the IBM. More important, it was affordable. We were living in Germany at the time, so one afternoon I called an independent Radio Shack outlet in Maine that advertised in the back of Byte magazine and asked if they would ship to Germany. They said 'sure!' and a few weeks later I had my first desktop PC clone.

Since the day that Tandy 1000 arrived, over 37 years ago, there's been a PC 'box' of some make or model on my home desk, wherever that desk happened to be.

But yesterday marked the end of that era. When I plopped my Surface Pro tablet down in place of my Dell desktop I realized I'd never be going back.

What I couldn't realize when I bought the Dell five years ago was that I didn't really need another heavy iron desktop PC. My computing habits and needs were rapidly changing and a good laptop would have filled the role just fine. I just couldn't see it at the time. But around 2020 I finally understood this and started contemplating my options. I kept the Dell desktop because it was paid for and working fine, but I was also starting to think about what I would do when it gave up the ghost. That time has come.

So farewell to the heavy iron PC, and all hail the mobile hybrid computing platform.

And hey, look at all this new free desk space!

W8BYH out

*Blue Screen Of Death - that infamous Microsoft crash screen that early Windows users loved to hate

No comments:

Post a Comment