- A design that emphasizes ruggedness, off road mobility, reliability and survivability

- Only a very minimum of 'bells and whistles'

- Powertrains optimized for rugged off-road performance

- A conscious selection of lower tech options (ex: coil spring suspension vs suspension air bags) to better fit the vehicle's mission requirements of reliability, mobility and survivability

- Virtually zero accommodation for 'lifestyle' options: entertainment systems, built-in wi-fi, seat-back entertainment systems, etc.

- An easily modifiable design

- A serious effort to keep the whole package reasonably affordable

15 July 2022

A Metaphor Of Sorts

10 July 2022

ARES Southeastern US Situational Awareness Map

This is a bit of a coming out party. So, noisemakers and party hats all around!

Last month I put up a post about the Situational Awareness Map, highlighting some changes I had made, and some future plans. Well I'm happy to announce that the map is now out of beta development and is available for general use. A lot of the changes are evolutionary, not revolutionary. But the changes and improvements are significant enough that a quick overview is warranted.

Perhaps the biggest change is that the map is now focused on the entire southeastern US, not just Georgia. I've talked with key users of this map for some time and the thought is that a regional focus makes more sense; weather systems and radio signals don't respect political boundaries, and we are often called on to support our fellow ARES members in adjacent states. But how do we define 'southeastern US'? Well, the most logical way is to follow FEMA, and use FEMA Region 4 as the definition. This makes a lot of sense since organizations like SHARES, DHS, CISA, NOAA, the Army Corps of Engineers and other federal agencies structure their disaster response frameworks in relation to FEMA regions. So FEMA Region 4 it is!

Other key improvements come in how the map (data) layers are structured in the map. Data structure is tightly focused around individual states. This give each state the ability to focus/display only the data pertinent to their states. There is a lot of regional/national data in the map, but that's only for map layers that by design must span the region. The best example is NOAA weather radar. This is a national-level data feed and it is impossible to segregate it out by state.

Another serious issue that is starting to push to the forefront is map performance. At this time there are over 45 separate data layers in the map, everything from severe thunderstorm warning polygons to PSAP 911 service areas. Every data layer, even if it's turned off, imposes a performance penalty in the map. Let's use the HIFLD fire/EMS station dataset as an example. This is a national-level dataset with tens of thousands of point (station locations). Before the map can display just fire stations in state of Florida it must first pull across the entire dataset, apply a dynamic filter against the data to select just fire stations that fall inside of Florida, apply a complex symbology rule against those points and then dynamically display them in the map so the fire station symbols remain the same size regardless of the zoom level the user selects. That's a lot of work to ask a web browser to handle. Multiply this one example by 45 or so data layers and you start to understand why map performance is an issue that must be carefully managed. This map is starting to push the performance limits of what Chrome, Firefox and Edge can reasonably handle. For that reason I've imposed some rules that users need to be aware of:

- With the exception of the Severe Thunderstorm Warning and Tornado Warning polygons (provided by NOAA) all other data in the map is turned off by default. When the map opens, it opens to a blank screen that shows just the state and county outlines. It's up to the individual user to tailor the map to his/her needs by turning on the data layers they want. Therefore it's very important that you review the available map layers and practice turning layers on/off

- Requests to add new data layers will require some serious justification from the requester. You will have to provide a compelling operational need for the data layer you are requesting. Remember, every data layer imposes a performance penalty. During real-world events like hurricane disaster response I'll add whatever data is needed without too many questions, but for non-operational use I'll have to be very selective about what gets added

- Data layers that don't get used will get dropped. I can track individual data layer requests, and if I see a particular data layer just isn't getting used, especially if it's a national or regional layer, it'll get deleted from the map

W8BYH out

08 July 2022

If The Big One Hits, Be In Syracuse!

Last month the Antique Wireless Museum released a 1951-era industrial movie made by General Electric that highlights how the city of Syracuse, NY used mobile radio for disaster response after a nuclear strike. Conveniently, General Electric's mobile radio division was headquartered in Syracuse, so this is really an early version of an infomercial. But it's a well done infomercial, and actually tells a useful story about how to create what we call today an emergency operations center, or EOC.

I'm surprised at how little has changed in terms of EOC operations between 1951 and today. Today we have fancier communications systems, software, computers, the internet, smartphones, and better looking firefighter helmets 😄, but most of the basic roles and functions we have in an EOC today were there in 1951. From that perspective the movie is quite interesting.

What I particularly liked was the use of an early 'GIS' (geographical information system) - a map table with push-pins around which all coordinating activity revolved. Today we have fancy computer-based GIS systems, but paper maps and pushpins are still in wide use. It's still a very effective way to maintain situational awareness.

I was also really struck by the emphasis the movie places on Amateur Radio as an integral part of any emergency communications system, and an integral part of EOC operations. Quite impressive, really.

So have a seat, strap on your way-back goggles, and enjoy EOC operations as they were over 70 years ago!

W8BYH out

07 July 2022

Something Interesting From Yaesu

Everyone else is jumping on the prognostication bandwagon, so why not me?

Yesterday the word came out that Yaesu is releasing a new HF rig in August. Called the FT-710, it appears to be about the size of the Yaesu FT-991A, but it's HF only (no UHF/VHF capability). Now, the 991A is no diminutive little mobile rig, and the 710, based on the announced specs, is actually just a smidge bigger all around, so this isn't a SOTA rig by any measure. Some have observed that this is likely Yaesu's newest 'entry level' SDR rig, and is likely designed to go head to head with the Icom IC-7300. That sounds about right to me, because the radio incorporates Yaesu's newest SDR technology (which is getting great reviews). What little we know of the feature set so far looks good:- High resolution touchscreen interface

- Build-in tuner

- A DVI port on the back (for out-boarding the digital interface)

- Two USB ports.

- SD card slot

What's NOT been released yet is any mention of a built-in soundcard interface. However, Yaesu makes mention of a 'Preset' mode for things like FT8, and since you need a soundcard to run FT8 I'm guessing the soundcard interface is there.

The things I don't see but would like, beyond the soundcard interface, are:

- Built-in GPS, and a GPS synched internal clock

- Some level of industry standard environmental protection such as IPX5

- A set of factory rack handles (a-la the IC-7200) would be nice, but if not I'm sure Portable Zero will be right along with a set

- Yaesu traditionally 'gets it' when it comes to back-lit buttons (Icom? Icom? Icom?). Let's see if they continue the tradition

04 July 2022

Chip Shortages - Still?!

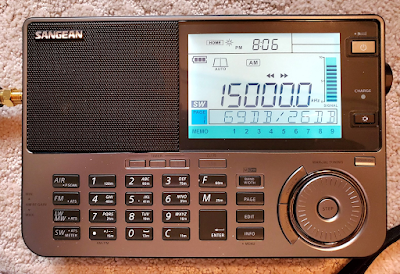

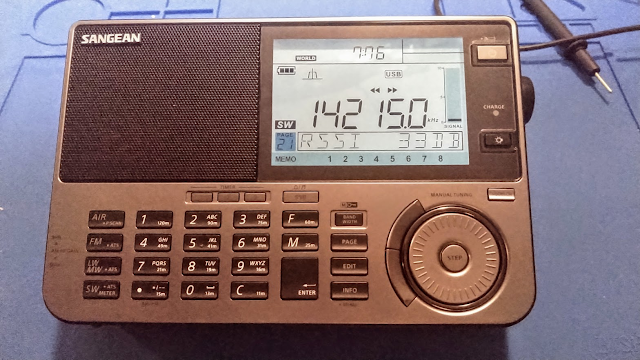

Thomas Witherspoon posted this a few days ago on his (excellent) SWLing Post blog:

Based on reviews of the radio in publications like Passport to World Band Radio (sadly out of print, and badly missed), I picked up an ATS-909 just before heading back to Germany in 1998 for my second tour of duty there. At the time Central Europe was still a 'shortwave rich' environment, with powerhouse broadcasters like Voice of Russia (the old Radio Moscow), Deutsche Welle, and the BBC still pumping out content on shortwave. Additionally, I knew that many of the German FM broadcasters were switching to RDS, making the ATS-909's RDS decode capability a neat and useful feature.

Reviewers really liked the improvements in the 909X2, but production was slow and prices for the radio, if you could find one, were high, with some retailers asking over $500. In the past six months production has increased, and the radio's price has settled down to about the $250 US level. Amazon now has regular stock of the radio and can deliver in a day or two.

One thing became abundantly clear to me in the few hours I've used this radio so far - the ergonomics and build quality are outstanding. Anyone who's spent any time with a portable SW receiver will find the controls clearly marked and well laid out. You don't need a manual to get up and running with this radio (but if you do, the manual is excellent).

Sangean includes an external wire antenna, ear buds, and something few other manufacturers provide - a 'wall wart' power cube. The radio runs off of four AA batteries and can use alkaline, NiMH and NiCad chemistry types.

A word about external antennas. Many manufacturers, including Sangean, include an external antenna with their radios. Many folks feel that a portable radio shouldn't need an external antenna. For commercial FM and AM broadcast reception, I agree. But for shortwave and ham radio reception, an external long wire antenna is absolutely necessary. You wouldn't expect your expensive Amateur Radio HF rig to operate well on 80 meters using a 3' whip antenna. Why would you expect a consumer-grade receiver to do better? Be realistic. If you buy a portable SW/HF receiver also pick up (or make) an external antenna to use with it.

22 June 2022

Message Center Clocks

I love clocks and watches, and I've written about this in the past. I also love to research and read about the history of radio, particularly radio operations involving two way communications (as opposed to broadcast radio, which is one-way only). It's clear that radio and time are inseparable. Just about everything in radio revolves around time. Our formal nets start and end at defined times. Much of our software like WSJTX and JS8CALL is tightly time dependent. Modern military and, increasingly, commercial transceivers are dependent on accurate time signals to synchronize things like frequency hopping, automatic link establishment, and automated digital messaging operations. Time is everywhere in radio. Has been since Guglielmo Marconi first thought about commercializing his 'invention' back around 1900.

My earlier post was about radio room clocks, particularly those that call out the mandatory quiet periods at 15 and 45 minutes past the hour. These clocks were designed specifically for maritime radio room use - a reminder to the operator to cease transmission for a 3-minute period and just listen on 500 kHz for any distress calls.

But there was another use for clocks in conjunction with radios, a use that was somewhat more utilitarian but just as important - in military message centers.

First, let's define what a message center is. A message center is nothing more than one or more radios dedicated to transmitting and receiving message traffic. If you were in the military for any length of time, particularly if you worked a job that involved coordinating activities at a brigade or higher headquarters, you'll have heard the terms 'comms (communications) center' and 'message center'. A comms center is an over-arching communications environment that handles both direct voice communications and message traffic, while a message center is dedicated to handling just digital or voice message traffic - orders, reports, etc. When a commander wants to talk by voice to one of his subordinate commanders he goes to a comms center. When he needs to send a report to his higher headquarters he goes to a message center. The difference between the two was often very fuzzy, particularly at the lower battalion and company levels, where one or two radios were handling ALL voice communications and message traffic duties. But at higher command levels, with steadily increasing volumes of message traffic, a dedicated message center was usually required.

And, of course, message centers needed clocks. Everything was coordinated by time. Radio message traffic needed to be time-stamped and logged with the time received or sent. Operators needed to know when to switch frequencies to handle message traffic on different nets. They needed to time-track when physical messages (paper copies) were received or handed off. Basically, everything in a message center revolved around time.

It was during WWII that the concept of a purpose-built message center clock took hold. There may be earlier designs, but if there are I have not seen them. My my guess is that prior to the WWII era militaries just used whatever cased clocks they could procure. But starting with the run-up to WWII (which, remember, started in Europe in 1938 - a full 3 years before the the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor), a few militaries like the US and Germany started specifying designs for message center clocks. Let's start with the US. The Army took the smart and easy path, and asked manufacturers like Chelsea, Hamilton, and Lowe to make a variation of the maritime 'deck clocks' they had been making for years. The first clocks were brass cased, later switched to a phenolic (Bakelite?) housing to conserve a strategic metal that was in short supply. The movements in these clocks were fairly rugged, simple to service, and were already in volume production. All the US Army had to do to make them 'army' was to have the words 'Clock Message Center M1 (or M2)' stenciled on the face. The M1 models had 4" faces, the M2 models had 6" faces, and most seem to have come with a secondary 'zulu time' hour hand. The Army had them mounted in a clever flip-open wooden box, which made them easy to transport and set up.

|

| Clock Message Center M1 (4" face) in a brass case. Brass was a strategic metal during WWII and clock cases were quickly switched to a phenolic (Bakelite?) case |

|

| The far more common M2 message center clock (6" face) in a phenolic housing. The red hand is the 'zulu' or second time zone hand |

These clocks were a commodity item, produced in the thousands. If they appear in period photos at all it's because the photographer was taking a picture of something else and the clock just happened to be in the shot. Here's one of the best known (and clearest) photos of a message center clock in use. This photo is interesting because it looks like the radio is being used in an early M2 or M3 Scout Car. Note the telegraph key strapped to the operator's leg, and the home made speaker box. I'd guess that this picture was taken either pre-war, or immediately after the US entered WWII. This is a great example of what a 'message center' looked like in small units during the war - a single radio, a single operator, a clipboard with some standard message forms, and a clock.

Some have asked, why not rely on wrist watches? A good question. We have to remember that prior to WWII a good quality wrist watch was a fairly expensive consumer item. Not everyone owned one. This was almost half a century before the arrival of cheap but accurate quartz watches. In the 1930's and 40's all watches were hand assembled mechanical units that could cost a working man's weekly wage, or more. Plus, the US military can not compel soldiers to use their personal property for official purposes - which means they can't compel you to buy and use a wrist watch as part of your Army job. If your job requires a watch, they'll issue you one. However, it's cheaper to provide a single clock that's available for all to reference than hand out a bunch of wrist watches. Then there's the issue of time synchronization. All activity in a message center had to be referenced to a single time source. If everyone is using their own wrist watches, and each watch is off a minute or two in either direction (very common with mechanical watches) then how are you sure that Message A arrived before Message B? In wartime this matters, a lot.

The German Army took a similar approach. Called a 'funkuhren' (radio operator clock), it was a standardized clock specifically designed to be used in message and communications centers. However, their clocks were a bit different - they appear to be large pocket watch movements in a modified case with a larger mainspring, giving an 8-day runtime. The whole thing is mounted in a wooden case, and the movement can swing out for winding via a knurled knob or stem on the rear. Actually a pretty good arrangement. since it doesn't require a winding key like the American clocks do.

|

| Note the 'funkuhren' on the table between the two radios |

So we've looked at US and German message center clocks from WWII. What about the British, French, Japanese, Russians, Canadians, etc? Honestly, I don't know. I've never seen any write-ups or on-line discussions of message center or radio room clocks in use by other countries involved in the war. I can only guess each country had some sort of standardized timepiece they adopted.

|

| A modern (quartz) interpretation of the classic US Navy deck clock, which was adopted by the US Army as 'Clock Message Center M2' |

|

| A modern Chelsea 'radio room' clock. I like this one for it's accurate quartz movement and 'zulu' or second time zone hand |

|

| My grandfather's Illinois Bunn Special pocket watch in front of a 6" Chelsea radio room clock |

And I think I've spied my solution, courtesy of Seiko. It's the Seiko SNE370 wrist watch. It's not as large as a pocket watch, but at 43mm it's it's plenty big enough. It's got a clean, uncluttered face with a 24 hour inner ring, and it's got an accurate quartz movement. I can do without the day/date readout, and I'd love a second hour hand (a 'zulu' hand or, as it's called in the watch world, a GMT hand), but you can't have everything. One problem though... it's out of production. Aaarrrgggghhhh! I can't catch a break.

18 June 2022

Decisions, Decisons

The XYL and I are beginning preparations for a week long camping trip later this summer. Of course radio will be part of the adventure. The question is, which radio(s)? If I look at the goals I have for this trip (beyond campsite setup and tear-down, meal prep, entertaining the XYL, walking the dogs, entertaining the dogs, feeding the dogs, general camper maintenance, shopping, talking with camper neighbors, sightseeing, etc, - those of you who camp know what's involved), the things I want to do with radio include:

- chasing DX

- POTA activations

- Winlink

- JS8CALL

- MARS

- SHARES

- testing & playing with ALE (Ion2G)

|

| IC-7300. The all-around champ in my radio stable |

|

| IC-7200. Not as capable as the 7300, but a good bit more rugged |

|

| Mag loop antenna - quiet and effective, but can only handle 25 watts |